- Published on

Devlog #61 - PxEngine

For years FO2's UI text pipeline was constrained by BabylonJS GUI, which ultimately relies on the HTML Canvas 2D API. Dynamic text there is extremely expensive because every update requires CPU rasterization and redraw, so even moderately changing text can tank performance. To work around this I switched to bitmap fonts rendered as small pre-baked images and simply blitted those onto the canvas instead of asking the browser to draw glyphs. Copying pixels is much cheaper than shaping and rasterizing text every frame, so this approach was noticeably faster, but it was still fundamentally bound to the canvas rendering path. It also came with significant limitations: each font size needed its own atlas, scaling introduced blur or distortion, memory usage climbed as more sizes were added, and the text could never be truly resolution independent. After years of managing those tradeoffs, it became clear that the real solution was to move text rendering entirely onto the GPU.

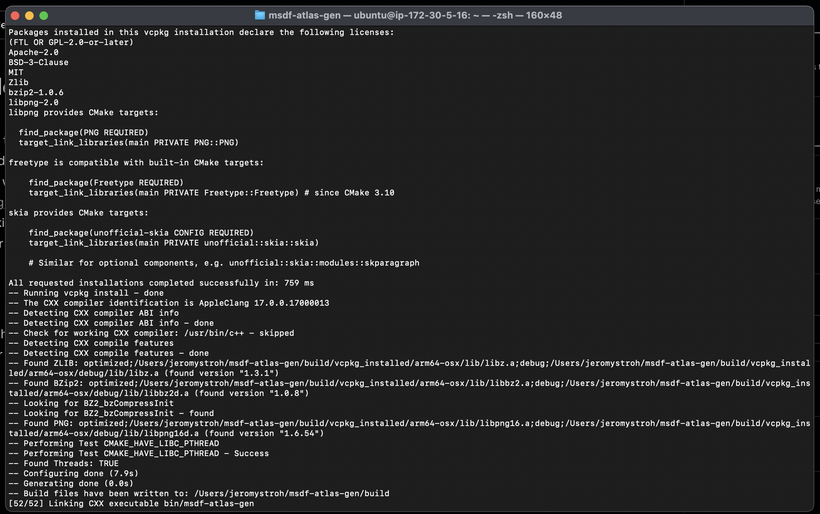

So to draw text in the new engine, we are going to start with multi-channel signed distance fields, which allow a single atlas to render clean, sharp characters at virtually any size while batching efficiently and avoiding the CPU bottlenecks of the canvas pipeline. I know that is a mouthful, but it is the piece that finally solves all of those earlier problems in one shot. First off we need an msdf generator and we get that from this repo https://github.com/Chlumsky/msdfgen. Actually we need an msdf atlas generator so we will be working with this repo https://github.com/Chlumsky/msdf-atlas-gen. There's no macOS build for this thing so I get to clone it and figure out how to build the executable binaries locally.

Whew, that was fun (not)! And now that we have the msdf atlas gen executables, we can run it over our lovely fffharmonyvx.ttf font and see what we get as output. But before we do that, we need to figure out which options are best for our font.

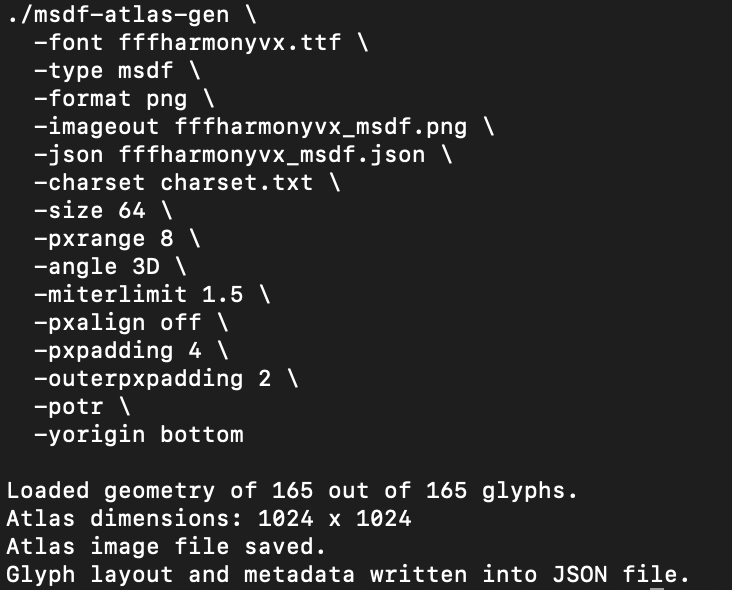

After inspecting the TTF data, it is clear the font was designed on an eight-pixel grid and uses hard, axis-aligned corners. We therefore want enough atlas resolution to oversample that grid so it remains stable under zoom and rotation, without wasting memory. A glyph size of 64 provides a clean oversample of the outlines while staying compact, and a pixel range of 8 supports stable edge reconstruction during scaling and animation. Pixel alignment is disabled to allow continuous transforms, and modest inner and outer padding are applied to prevent sampling bleed under linear filtering. Together, these settings yield crisp corners, stable animation, and consistent results from very small text through large on-screen rendering without unnecessarily increasing atlas size. And with that we now have a json file and a png file for our newly created MSDF font.

This is the MSDF font image file. It looks a bit wacky because it is not storing normal grayscale glyph shapes but encoded distance data split across the RGB channels. Each color channel represents the signed distance to a different edge of the glyph so the shader can reconstruct sharp corners at render time. The strange color fringing and overlapping gradients are intentional and are simply how that edge information is packed into the texture. It is not meant to be readable as an image, it is meant to be decoded by a shader, and once rendered it produces clean corners, stable outlines, and consistent results across scaling and animation despite the odd appearance of the raw file.

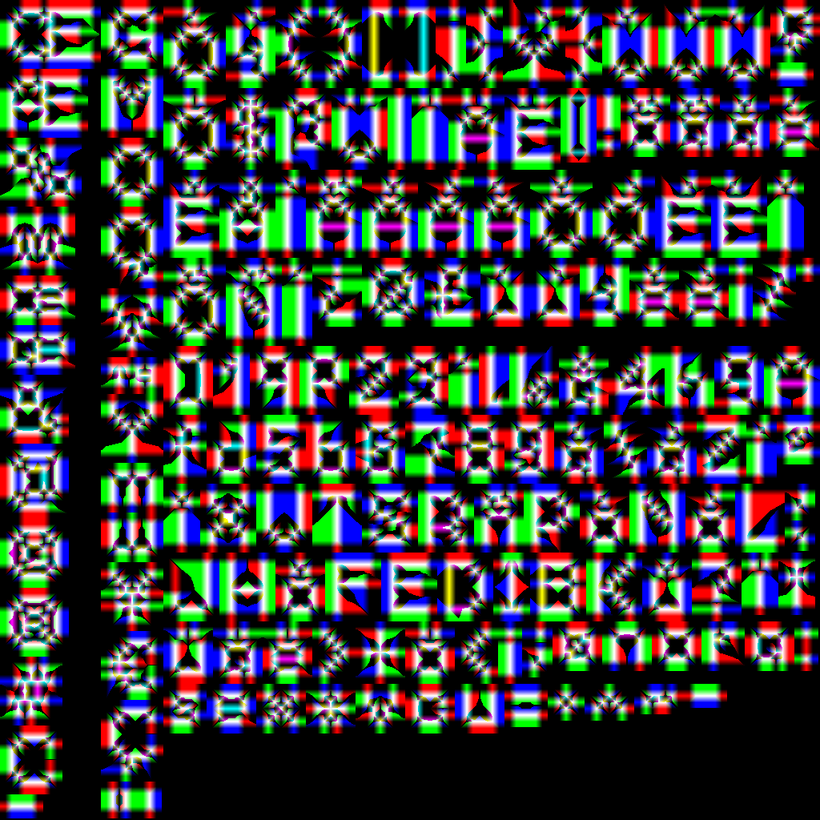

So now that we have our TTF font converted to an MSDF font we're ready to load it into our engine. The font consists of a png image file and a json data file. As you can see our load function tells the browser to grab the json and the png image in parallel on background threads. It also decompresses the png into a bitmap on a background thread. Then once we have both the json and the bitmap data in memory, we parse out all the json data into a font data class and upload the bitmap into GPU memory!

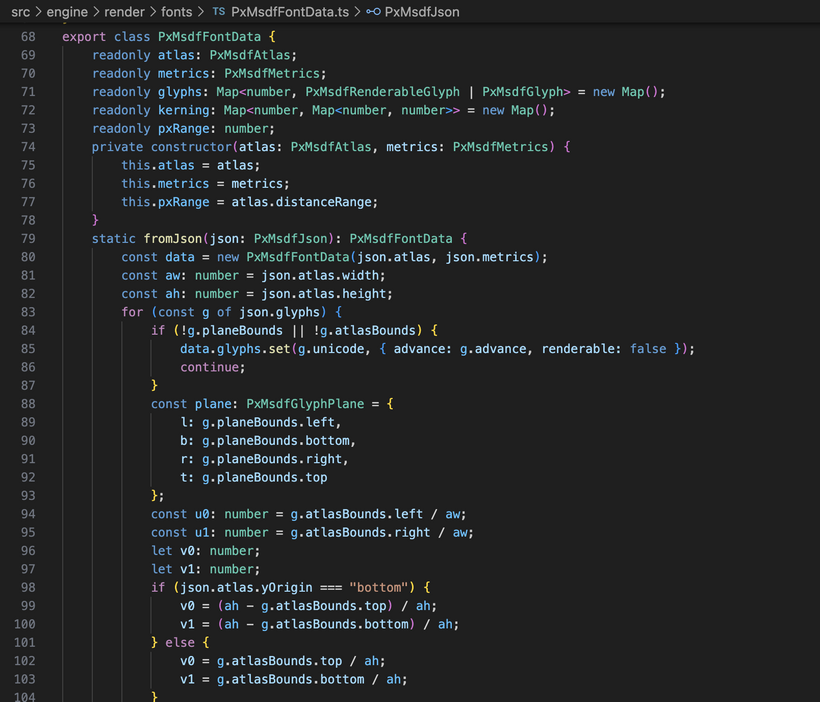

I’m going to skip over talking about parsing the MSDF json data into a class usable for laying out text as it’s just really boring and tedious. All it really does is turn that big descriptive blob into something the renderer can use quickly at runtime by extracting the per-character metrics, texture coordinates, spacing information, and global font measurements, then organizing it into lookup tables keyed by Unicode. This tells the engine exactly where each glyph lives inside the atlas, how big it should be on screen, how far to advance the cursor after drawing it, and how certain letter pairs should be tightened or loosened so text does not look robotic. Once that data is packed into a compact in-memory structure we never have to touch the raw json again, and the rendering code can just grab what it needs per character and spit out quads for the GPU, which is ultimately what lets us draw crisp, scalable text efficiently without doing any heavy work during gameplay.

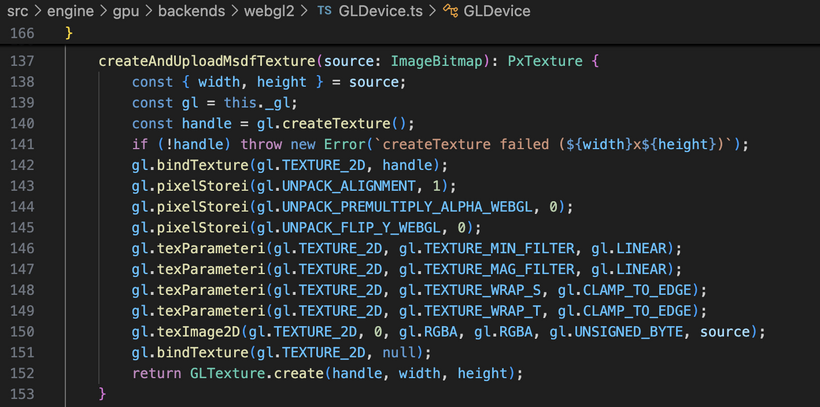

And here’s how I upload the MSDF font atlas as an ImageBitmap into GPU memory using WebGL2. The gl variable is the WebGL2RenderingContext from the HTML canvas element. In WebGL you create a texture object, bind it as the active TEXTURE_2D, configure the pixel unpack state so the data is interpreted correctly, set the sampling and wrapping parameters, and then call gl.texImage2D to transfer the bitmap into the texture’s storage on the GPU. After the upload completes, the texture lives in GPU memory until it is explicitly deleted.

And this is where things start to get really complicated.

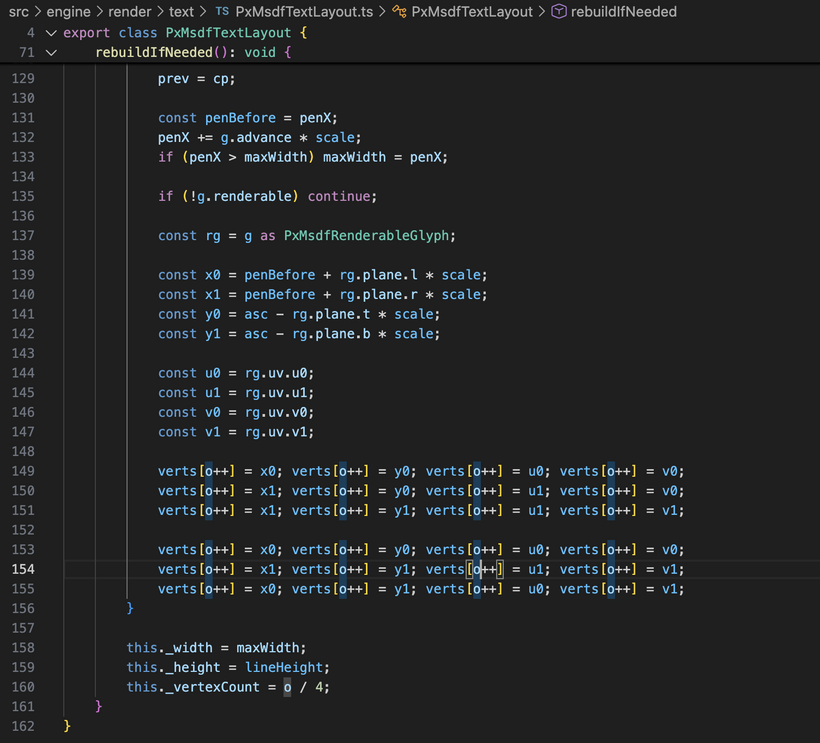

PxMsdfTextLayout takes a font and a piece of text and converts it into a set of vertices the GPU can draw. It tracks the text, size, and range, and only rebuilds the data when something changes. When needed, it steps through the characters, positions each one along a baseline using the font’s spacing rules, and generates a rectangle for every visible glyph with the correct texture coordinates from the atlas. The rectangles are written into a buffer as triangles, producing a ready to render block of geometry. It also measures the overall width and height of the text so the engine knows how much space it will occupy on screen.

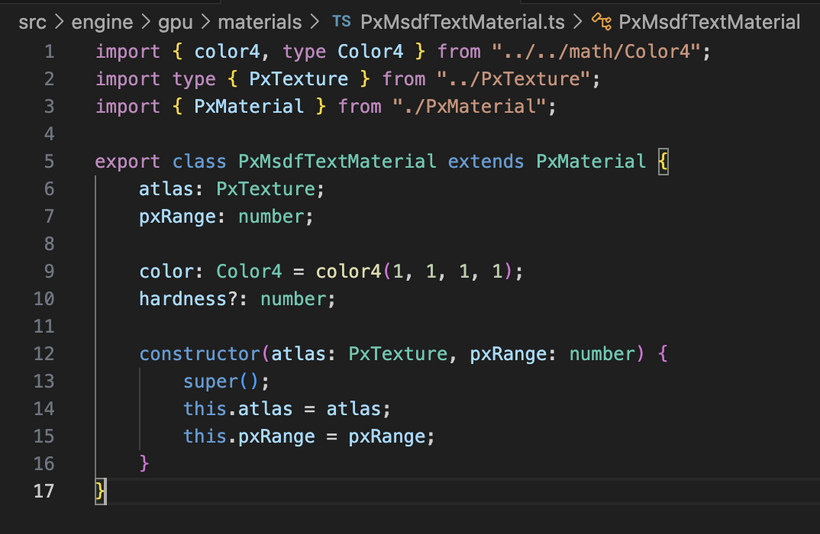

To keep rendering flexible, the engine uses a material system that describes how something should be drawn rather than what it is. A material bundles the GPU resources and parameters needed by the shader, such as textures, colors, and tuning values, so different objects can share the same rendering code while still looking different. The MSDF text material is a specialized version that holds the font atlas along with color and distance field settings, allowing any text geometry to be rendered with crisp, scalable edges simply by supplying this material to the renderer.

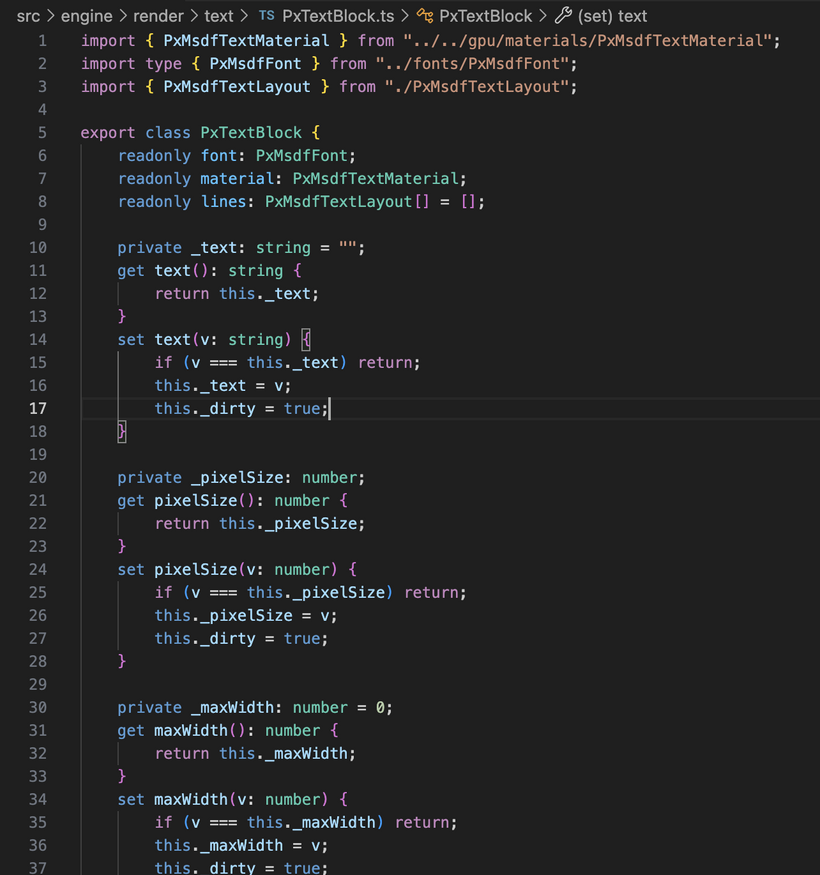

PxTextBlock is the object that turns a plain string into a multi-line piece of text ready to render. It holds the font, creates the text material, and manages a list of line layouts. When the text, size, or width constraint changes, it rebuilds by splitting the string into lines based on explicit breaks or wrapping rules, trimming extra whitespace, and updating each line’s layout. Once finished, it knows the final dimensions of the block and has all the per-line geometry prepared so the renderer can draw the text as a single coherent unit.

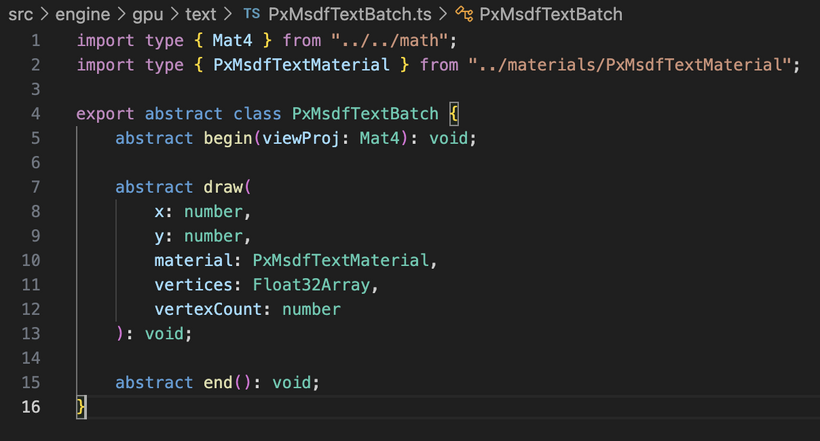

PxMsdfTextBatch is the renderer side component that actually turns all that prepared text data into draw calls. It works as a specialized batching system for MSDF text, collecting many glyph triangles into a single dynamic vertex buffer so they can be rendered efficiently in one go. Each frame begins with a begin call that supplies the view projection matrix, followed by a series of draw calls that append transformed vertices using a particular text material, and finally an end call that flushes everything to the GPU.

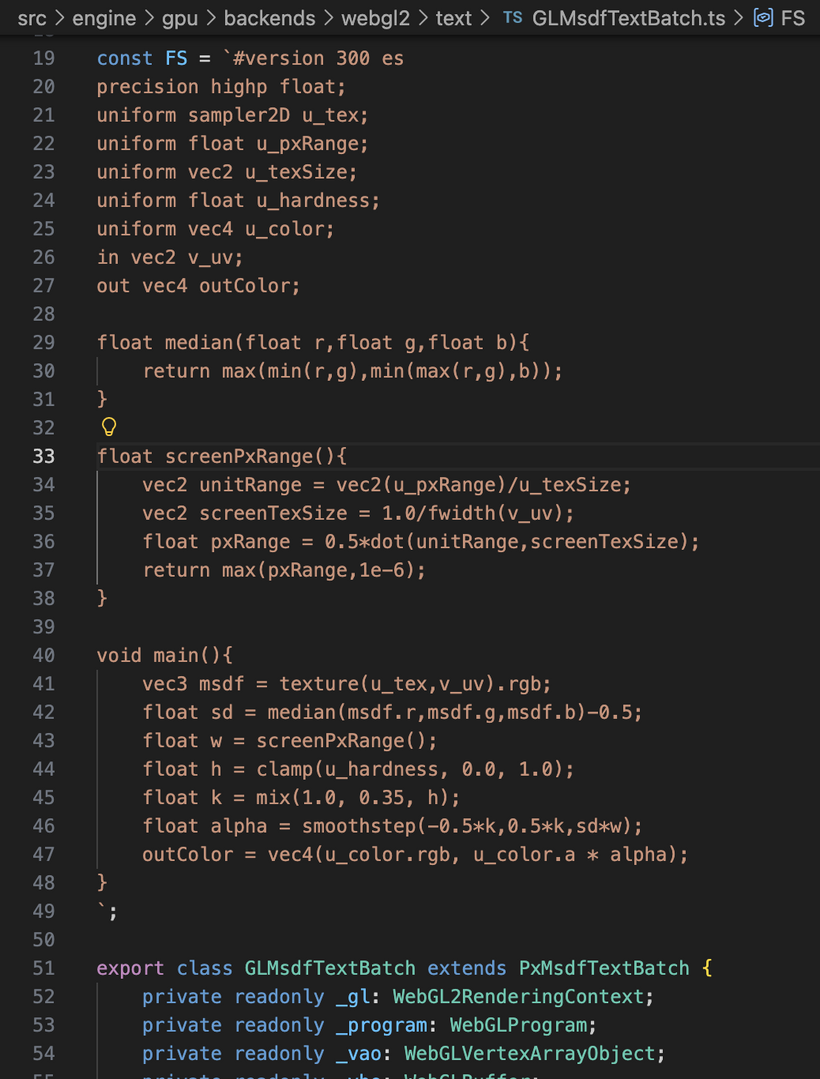

The WebGL2 implementation compiles the MSDF shaders, sets up a vertex array and buffer, uploads the accumulated vertex data, binds the font atlas texture, and renders the triangles with blending enabled. By grouping characters that share the same material and delaying the actual draw until flush time, the engine minimizes state changes and draw calls.

All of these parts come together during rendering to turn a plain string into fast GPU work. The application hands text to a text block, which uses the font metrics to build line layouts and per-glyph geometry. That geometry is sent to the MSDF text batch along with the material that holds the atlas texture and rendering settings. The batch gathers triangles from many glyphs and many text objects, applies transforms, and submits them in as few draw calls as possible. On the GPU, the vertex shader places each quad in the correct position while the fragment shader samples the MSDF atlas and reconstructs sharp edges from the encoded distance data so the characters stay crisp at any scale. Since layout and geometry are only rebuilt when the text actually changes, and since all glyphs share the same texture and shader, the engine can push a huge amount of text without slowing down, even while everything is moving, scaling, or rotating.

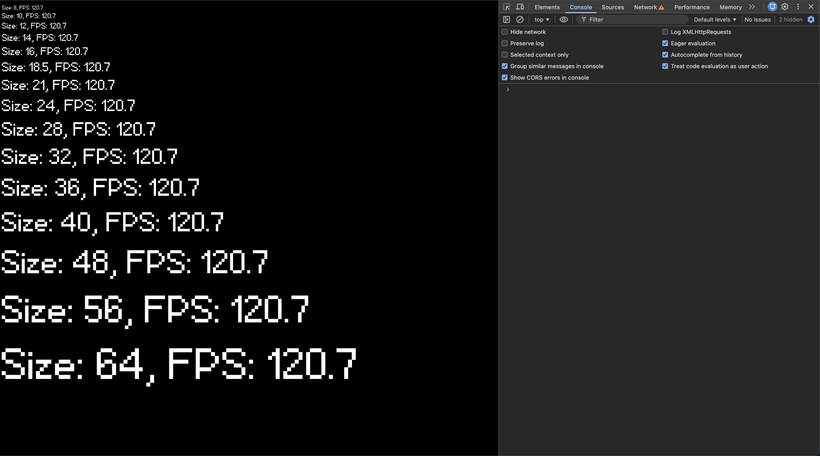

To validate the pipeline, I wrote a small test harness that loads the MSDF font, builds a Canvas2D scene, and then spawns a stack of PxFpsTextNode instances at a range of pixel sizes from 8 up through 64. Each node renders its own FPS readout using the same atlas and material, so in one frame we are exercising the layout code, the per-line geometry generation, and the MSDF batching path across a wide range of scales. The result is what you see in the screenshot above: the glyphs stay crisp and consistent at every size.

Now that text is finally on the GPU, I can stop treating UI like a special case and just build a real 2D scene graph. The goal is simple: everything on screen is a node. Nodes can have children. You change a few properties on a node and the system figures out where it lives, how big it is, and what transform it ends up with. Then rendering is just a tree walk that feeds rectangles into a rect batcher and glyph quads into the MSDF text batch.

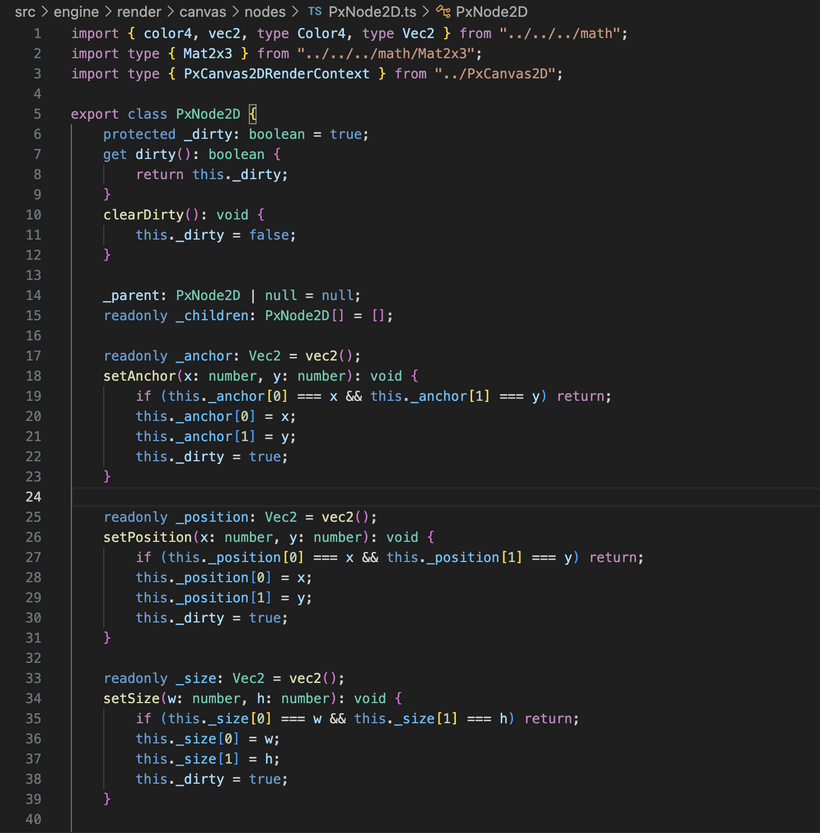

PxNode2D is the base building block. It holds the handful of values that actually matter for 2D layout and transforms: anchor, position, size, pivot, scale, and rotation. Anchor defines where the node attaches to its parent, expressed as normalized coordinates inside the parent’s rectangle. Pivot defines the point inside the node’s own rectangle that scaling and rotation occur around. Position is the pixel offset from the anchored point, and size defines the node’s local width and height.

Those values are not just for drawing. They directly drive layout. During the layout pass the engine resolves size, computes the anchored offset inside the parent, applies the pivot adjustment, and writes the results into a localPosition and localSize. From that point forward, rendering code does not need to re-evaluate layout math. It simply consumes those cached values and builds transform matrices.

The dirty flag ties the whole thing together. Every setter on PxNode2D marks _dirty when a layout affecting value changes. PxCanvas2D.layout() then walks the tree iteratively and only recomputes nodes that are dirty, or nodes whose parent changed during that pass. If nothing changes, nothing is recomputed. As the UI grows, this keeps layout cost proportional to actual edits rather than total node count. Most nodes remain stable most frames, so the system scales cleanly even when the scene graph becomes deep or wide.

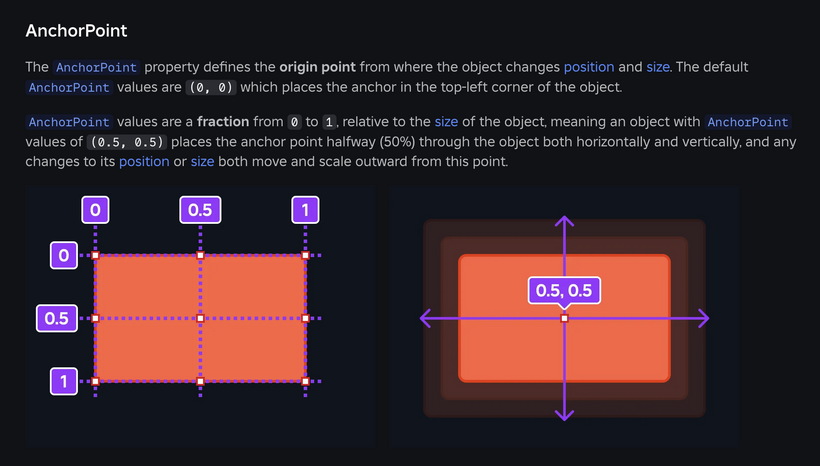

The Roblox creator documentation actually has a great explanation of what an anchor is as you can see in the image above. https://create.roblox.com/docs/ui/position-and-size

And then in the Aseprite documentation there is a great explanation of what a pivot point is. That point that you see move around in the gif above is where position, rotation, and other properties are applied to! https://www.aseprite.org/docs/rotate#rotate-sprite-or-selection

Whew, that was a lot of work for one week. How about we create this week's demo and have a rest.

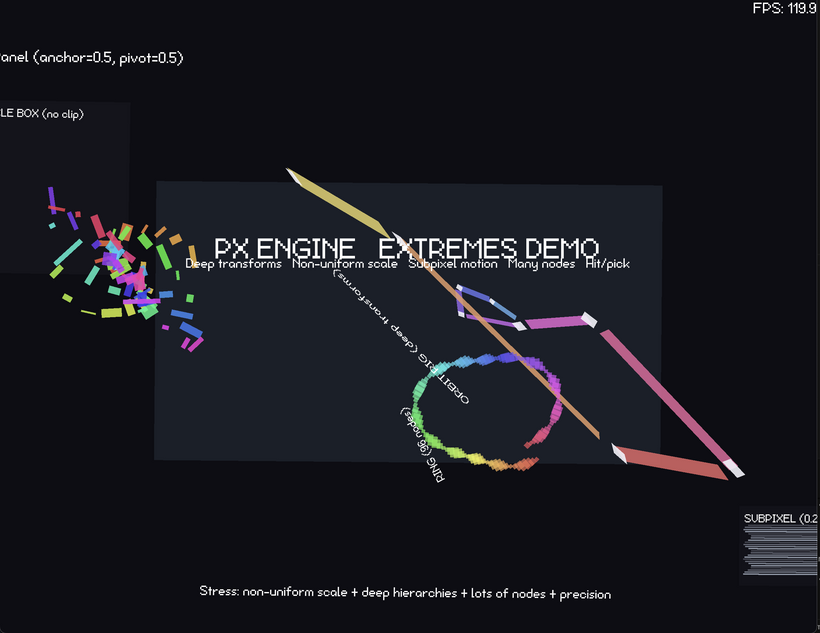

https://pg-renderer.vercel.app/

So this week’s demo is basically a stress scene to prove the new 2D system actually holds up under real use. When the page loads it pulls in the MSDF font, attaches an FPS counter to the root, and then builds a large reference panel in the middle of the screen. Inside that panel are several groups of animated nodes designed to exercise different parts of the layout and transform code. On the left is a box filled with many small colored squares moving along independent paths while rotating and scaling, which quickly drives the node count up. On the right is a deep transform chain where rectangles are parented end-to-end so motion compounds down the hierarchy, forcing anchor, pivot, rotation, and non-uniform scale to interact across many levels. There is also a large ring of nodes orbiting around a center point, and a small subpixel test where thin bars move in fractional pixel increments to expose precision issues. All of it runs continuously, so what you are seeing on screen is the scene graph, layout pass, transform propagation, batching, and MSDF text rendering all being hammered at once while remaining stable and responsive.

And that's it for the first week of the Pixel Engine. We've made huge progress thanks to me staring at GUI engine code across many engines on and off for the past 20 years!

See you on Friday for the next patch notes and then again on Sunday for the next devlog!

Have Fun & Keep Gaming!